The prospect of being able to see arguably the most iconic piece of nautical history is a powerful and enticing one; so enticing, in fact, it can factor in to a company making dangerously unsafe decisions that ultimately lead to the swift yet grizzly deaths of five people.

Backstory

OceanGate, Inc. was founded in 2009 as a privately-owned company in the United States by two men: Stockton Rush and Guillermo Söhnlein. Stockton was born into a rich family and decided to focus on the deep sea after space exploration lost its appeal to him.

In 2017, he told journalists: “I wanted to be Captain Kirk and in our lifetime, the final frontier is the ocean”. Given how little of the ocean has been explored since boats and submarines were first invented, it sounds like a reasonable goal which is shared by many people across the world.

Hence, OceanGate was born. The mission was to allow people to experience deep-sea travel to shipwrecks, underwater canyons, and the like. Rush was at the helm of the company and always ensured passion flowed in everyone working there.

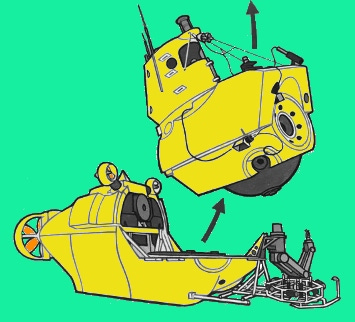

Three submersibles were built – Cyclops 1, which aided in the mapping of the Andrea Doria shipwreck, Cyclops 2, and the Titan. Cyclops 1 went down only 240 feet, but was rated to dive up to 1640 feet. Expanding on this, Cyclops 2 was built to dive up to 4,000 meters (13,123 feet) deep and carry five people.

In 2018, the cracks began to show. Several submarine development specialists penned letters to Mr. Rush warning him of the lack of proper certification for the Titan. The director of marine operations, David Lochridge, noted potential dangers for the Titan at such a depth. Subsequently, OceanGate fired him, claiming wrongful release of confidential information. He sued in response. The New York Times reported that the court documents indicated he knew that the Titan’s viewport window was built to withstand pressure at down to 1,800 meters. The Titanic shipwreck rests at 3,800 meters.

Additionally, in 2020, financial records show that Rush and fellow directors on the OceanGate board sold a stake on the company worth 18 million dollars. Interesting, given each passenger was charged $250,000 each for a trip on the Titan. Given its global infamy, it’s no surprise why the Titanic shipwreck was chosen as the perfect underwater location to grab their interest.

Sal Mercogliano, a former merchant mariner, and maritime historian at Campbell University, stated that submersibles do not fall under any governmental safety regulation board (like the FAA with aircraft), and it is up to their engineers to register them with a third-party nautical certification society. The American Bureau of Shipping is one of them. Only one of OceanGate’s submersibles were inspected by them – and it wasn’t the Titan. The Titan had no registration – as a U.S. vessel, with international agencies, or even with any maritime engineering industry groups.

“The intensive time-consuming process of scheduled inspections and certifications is a slow-down and barrier to innovation and exploration potential” – was cited as a reason by Rush to cut back on high-level testing and qualification of the Titan submersible. According the the CBC, OceanGate’s website had a blog post that literally read: “Bringing an outside entity up to speed on every innovation before it is put into real-world testing is anathema to rapid innovation.”

Furthermore, the dive point for the Titanic shipwreck site is outside of the marine boundaries of both Canada and the United States. Hence, the Titan was operating under an experimental classification in unregulated waters, but was marketed as a tourist vessel to its high-ticket customers.

A Look at Submersible Design

The first in-person viewings of the Titanic shipwreck were done in 1986 with Alvin, aka DSV-2, built by the United States Navy and operated mainly by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI):

Its pressure hull is in a spherical shape with 2-inch thick solid titanium, with just enough space for three people. This ensured that the water pressure would be equally applied at every point, omnidirectional. It had three dinner plate-shaped viewports – two on the side and one at the front. Periodically, the sphere underwent a six-month-long overhaul about every three years:

The air system was built to allow for up to nine hours of operation. It was built in two parts – the outer body and the sphere. In case of an emergency, the sphere part could be immediately disconnected and rise straight up to the surface:

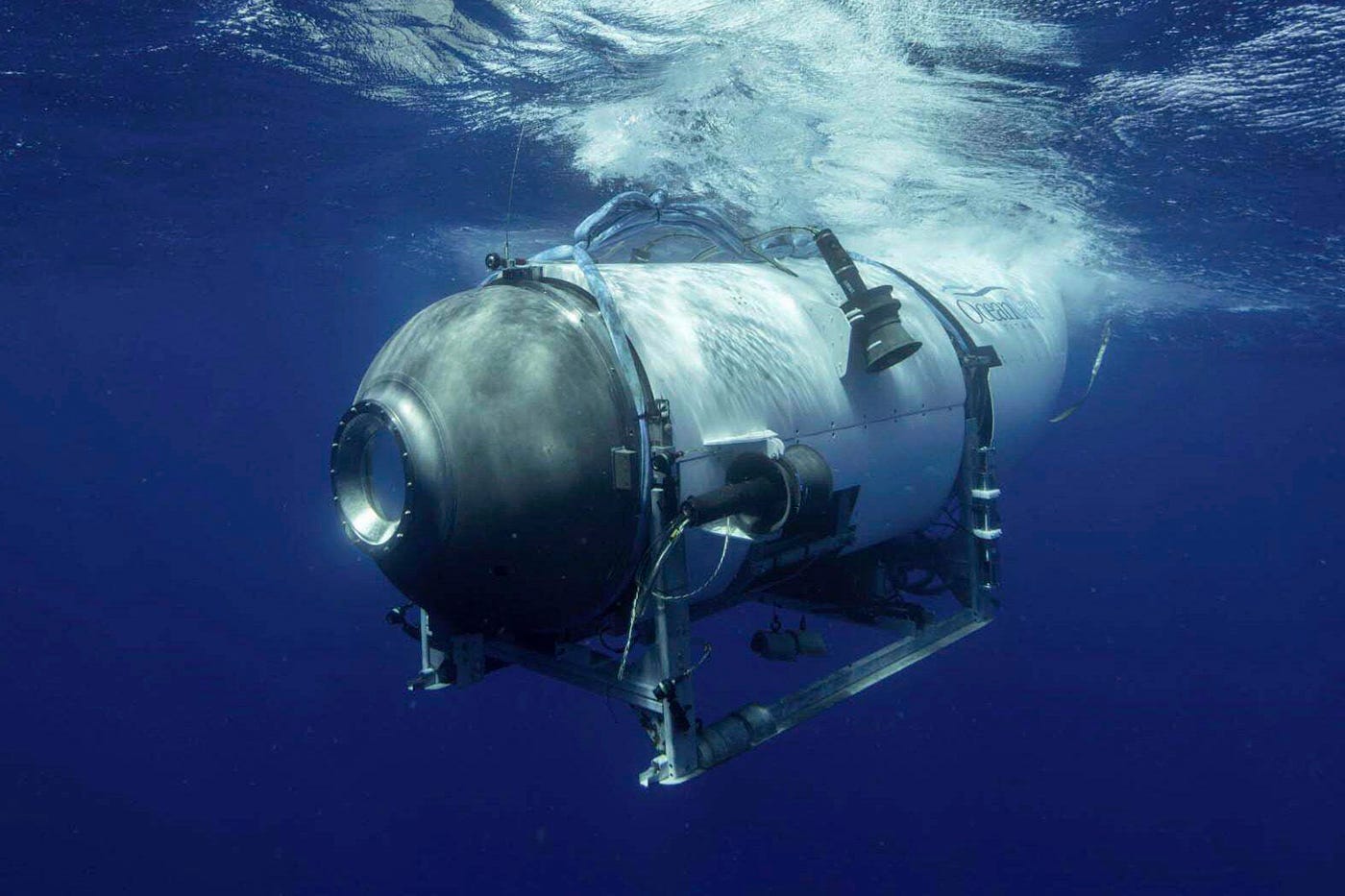

Now, let’s look at Titan: The hull was cylinder-shaped, with a tapering cone tail and a titanium bowl-shaped front, with a singular large, flat, front-facing viewport:

If you know anything about pressure distribution, a cylinder is not omnidirectionally distributed. Jasper Graham-Jones, an associate professor of mechanical and marine engineering at the University of Plymouth in the United Kingdom, spoke on this:

“Elongating the cabin space in a submersible increases pressure loads in the midsections, which increases fatigue and delamination loads. Fatigue is like bending a wire back and forth until it breaks. Delamination, is like splitting wood down the grain, which is easier than chopping across the grain.”

The idea was to simply mount a bunch of sensors around the pressure hull and analyze the effects of changing pressure on the fly. Before its ill-fated passenger voyage, the Titan had been on over 24 dives prior, which would inevitably produce stress concentrations and weaken the hull.

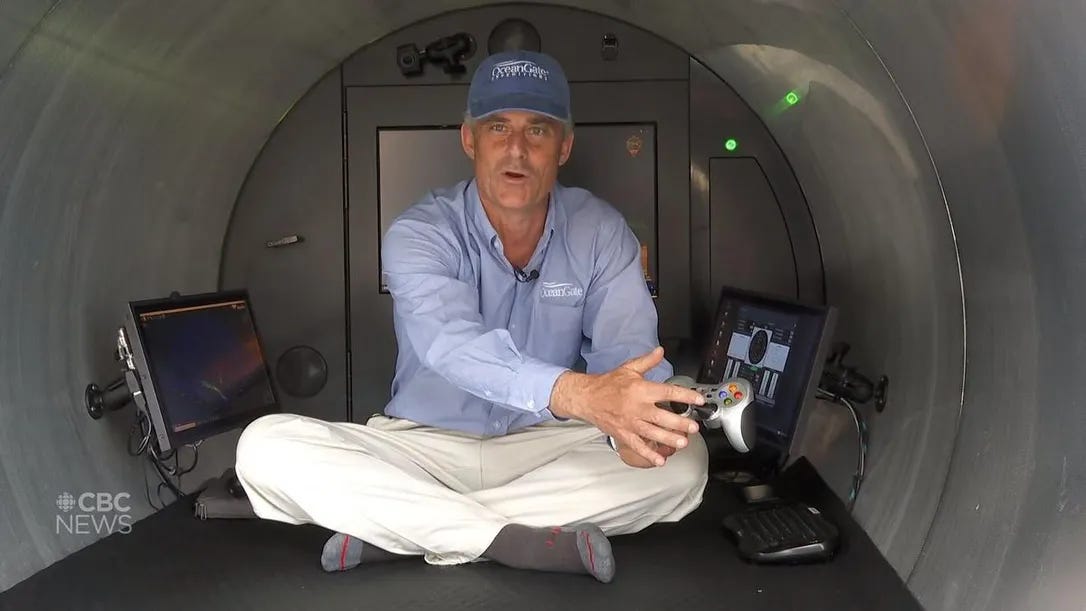

Later reports uncovered that Rush had merely obtained the hull using scrap carbon fibre from Boeing, and added titanium to give a sense of strength. OceanGate boasted an underwater run-time of 96 hours, with five people onboard. Steering was done electronically using a Playstation game controller and an array of computers, as shown in this still from a demonstration video Rush gave to CBC News. Lights, handles and propellers were all off-the-shelf parts, and the ballast was made with lead pipes.

Pause and re-read the comparison I’ve just made. It only stands with reason that this whole mission was doomed to fail from the start.

The Tragedy, Day by Day

On June 18, 2023, the Titan submersible was towed out by a Canadian boat to the North Altantic, 400 miles off the coast of Newfoundland. The boat and Titan maintained contact for 105 minutes, before losing connection. This wasn’t the first time it had happened. Just two years prior, in 2021, Brian Weed, a camera operator for Discovery Channel’s “Expedition Unknown,” partook in a test dive on Titan, and propulsion systems, computers, and comms all malfunctioned. Four 10-hour dives were conducted in 2022 – and the host ship-to-submersible communication was lost each time.

On June 20, 2023, Canadian aircraft detected underwater noises, which prompted the release of ROVs (remotely operated vehicles) to investigate at the pinpointed sources of the noises.

On June 22, 2023, the ROVs located the Titan’s tail cone about 1,600 meters from the bow of the Titanic, providing a sound conclusion that the submersible had indeed imploded, killing all on board.

To give a sense of this by numbers: Water pressure at 3,800 meters of depth is around 4,000 psi, or about two hundred times greater than that of a car tire. Implosion of a cylinder at that pressure would occur at a speed of 1,500 km/h, and be over in just a single millisecond. It’s nothing short of a miracle that the Titan’s structure, as shoddy as it was, somehow held up for 20-plus dives as it internally deteriorated. Furthermore, such pressure would pulverize the occupants’ bodies to dust, as it did for the Titanic ship’s passengers, so recovery of their bodies is all but impossible.

With the dust settling, lawsuits will inevitably be filed against OceanGate, though it may be hard for the families of the Titan tragedy to seek accountability and/or compensation, as all who boarded the Titan had signed a legal waiver stating they fully accepted the risks involved.

Final Thoughts

Water pressure – especially of the aforementioned levels – is not something to screw around with. There’s no room for shortcuts of any kind. The fault of this tragedy is clear and concise: Stockton Rush and his engineering team cut corners and deliberately ignored warnings from marine professionals regarding the structural integrity and mechanical reliability of their aquatic developments. The desire and ego for being innovative and groundbreaking surpassed and overshadowed their wisdom to put every stage of their submersible development through a full range of tests, let alone oversight when designing the shape and form of their submersibles to begin with.

Deep-sea diving, regardless of intent, is incredibly dangerous on all fronts. It still baffles me how there does not exist a United States or Canadian law, let alone an international law, to strictly regulate and oversee the production and usage of any ocean-going submersible within a country’s waters. The safety of ocean-lovers, shipwreck enthusiasts, and marine biologists alike can only be truly guaranteed with a set of firm engineering standards and federal law applied to all who dare to build submersibles for the uncharted depths, so that the reckless actions of Rush and his team are never repeated again.

“If I were to get us stuck and was unable to free the sub, we would become a bit of Titanic history ourselves.” – Will Sellers, former Alvin submersible pilot

May the souls of Hamish Harding, Shahzada Dawood, Suleyman Dawood, and Paul-Henru Nargeolet rest in peace.

Sources

Holly Honderich, C. M. & J. C. (2023, June 25). Titanic sub firm: A Maverick, rule-breaking founder and a tragic end. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-66014565

Cooke, R. (2023, June 21). Marine group says 10 subs in the world can dive to Titanic depths. Titan is the only one not certified | CBC News. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/oceangate-warned-2018-david-lochridge-1.6883432

Boyle, A. (2016, December 10). Oceangate starts building submersible craft that can take crews 13,000 feet deep. GeekWire. https://www.geekwire.com/2016/oceangate-submersible-cyclops-2-construction/

Finley, B. (2023, June 24). Titan sub disaster brings focus on murky regulations of deep-sea exploring – national. Global News. https://globalnews.ca/news/9788471/titan-sub-implosion-deep-sea-regulations/

Pratt, M. (2023, June 23). How the unconventional design of the Titan sub may have destined it for disaster. WSPA 7NEWS. https://www.wspa.com/news/national/ap-us-news/scrutiny-rises-on-titan-subs-unconventional-design-after-deep-water-disaster/

Chang, C. (2023, June 21). The Murky Regulations Governing Submersibles. Curbed. https://www.curbed.com/2023/06/oceangate-titan-submarine-unregulated-tourism.html